|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|||||||

| MySQL Users Conference April 18 - 21, 2005, Santa Clara, CA | |||||||

|

|

RoboGames 2005

by Quinn Norton |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Related Reading

Building and Programming LEGO® Mindstorms™ Robots Kit |

A sensor board coordinates data from two infrared controllers at 45° and 135° (angled to give some advanced data about the angle of the walls just in front of the robot). The sensor board also takes in data from a front-mounted sonar unit that tells the robot how far away the wall is (bumping a wall in the Trinity challenge is a penalty). Finally, there's a pair of line detectors pointing at the floor. These allow it to see the lines that mark the entrances to rooms, as well as the fire circle and the starting circle.

The last part of Larson's basic board kit is the CPU board, which pulls in data from the other boards, and spits out decisions to the motor.

Many of the decisions about what the sensors are seeing is farmed out to processors on the other boards, which come to an agreement using a subsumption architecture, the distributed decision-making architecture invented by Rodney Brooks in the 1980s. But at the top, the CPU board's Microchip PIC CPU (a 18F6621) uses a traditional maze-solving routine to map its way to the candle.

As maze-solving algorithms go, Larson chose the simplest. His firefighter uses right-hand wall following. The strategy works for the competition's standard maze--except for one room. That room thankfully didn't come up for Larson.

All of this is tied together over an I2C bus, the cheap two-wire serial bus used wherever good (but stingy) sensor systems are found. If you've ever read the temperature of your PC's CPU or fan speed, for instance, there's a good chance you've used SMBus, a variant of the I2C built into many modern motherboards.

The advantage for Larson of having a standard kit is that he can quickly improve his system for specific tasks. One extra board in his setup provides his robot with some specific firefighter skills. The board carries a 2kHz tone sensor, which launches the robot when a sound simulating a fire alarm goes off, and a Hamamatsu omnidirectional fire sensor (an off-the-shelf commercial unit that detects the specific wavelength of light a flame emits). Precise location is managed with an Eltec pyroelectric sensor, a point-sensitive device that can tell if the fire is right in front of it. The board sweeps the pyroelectric sensor around to locate the exact direction of the fire, then activates a simple relay for turning on and off a fan mounted to the front of the robot.

Larson's FlameOut is the very model of a modern competing robot. Simple, cheap, and straightforward at every layer, it builds up to become quite the complex beast. Altogether, it has ten CPUs working in coordination--a complete autonomous firefighter robot.

Clever, but not quite clever enough. The firefighter gold winner was 12-year-old Tony Pratkanis, also a HomeBrew Robotics club regular. His modified Grandar AS-M robot, lovingly known as "Solenopsis invicta" (named for a red fire ant), had both left- and right-wall following, giving it just the edge needed over Ted Larson's Flame-out.

Many software efforts have been accused being a solution looking for a problem, but some robotics engineers pride themselves on working on solutions to problems they hope exist soon. The ribbon climbing event, in which contestants try to built tiny robots that can climb a six-meter ribbon only 30mm wide, is a perfect example of the infectious optimism inherent in the RoboGames.

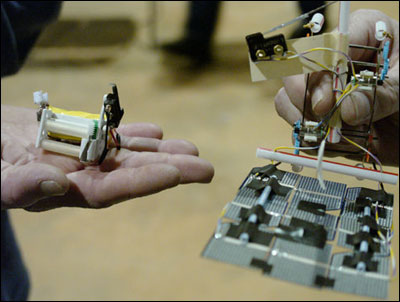

Ribbon climbers (Photo courtesy of Jeremy Fitzhardinge)

Ribbon climbing doesn't lead to the most sophisticated of autonomous robots--in fact, this year's gold medalist was largely a construction of piano wire and a drinking straw--but it seeks to solve one of the most novel of problems at the RoboGames, or indeed in robotics: the logistics of traveling up a carbon nanotube space elevator into orbit.

As simple as these little robots are, the challenges they face are uniquely tricky. Allow your robot to list to one side, and the ribbon can bunch, sending your robot back to earth in a hurry. Indeed, ribbon climbing is a ballet of balances, between weight and power, the friction to hold on against the friction blocking you from climbing, and a host of other artificial restraints that make the contest more complex and, hopefully, more applicable to the real world, including a remote transmission requirement and a five-second pause with automatic restart.

Nick, the builder of the first space elevator robot, has a safety lock built in. "In case [the robot] loses power, it has a ratcheting system that makes its own weight push down on the ribbon," effectively locking it into place. While not a contest requirement, Nick feels that this kind of a feature would be more practical in the real world. "Some people bend the cable, but I don't, because I don't think that's how it would work."

The contest winner, the drinking straw/piano wire affair, flapped a giant solar wing groundward, where its operators shined six high-power flashlights up at it. It raced up the ribbon in 25 seconds, including their five-second pause. It was so different from a super-heavyweight combat robot, it was hard to believe that these were, technologically speaking, the same species.

David Calkins was happy watching these disparate groups rub elbows. Some of the newer events began to bridge the cultural chasms that have plagued robotics in a more obvious way. The SRS Robo Magellan, a sort of mini DARPA Grand Challenge scoped to a university quad rather than a vast tract of southwestern desert, attracted university teams that rarely find themselves competing against or talking to the hobbyists.

Exhausted after three days of running the event, and many other intermingled conversations, Calkins still has enthusiasm to chat cheerfully about a combat veteran he had spotted who has returned home to build a human-like Robo One, and a delicate little sumo. Ideas have been shared; designs have interbred. Calkins has brought his robotic future a little bit closer.

Quinn Norton co-writes the ambiguous blog, runs a community co-op server, makes Yixing teapots, and writes about technology. For Quinn, every day is Take your Daughter to Work Day.

Return to the O'Reilly Network.

|

||||

|

Knoppix Hacks is an invaluable collection of one hundred industrial-strength hacks for new Linux users, power users, and system administrators using--or considering using--the Knoppix Live CD. These tips and tools show how to use the enormous amount of software on this live CD to troubleshoot, repair, upgrade, disinfect, and generally be productive without Windows--without the difficulty of installing Linux itself. Read sample chapters online: | More Safari Bookshelf results: | |||

Sponsored by:

|

Contact Us | Advertise with Us | Privacy Policy | Press Center | Jobs Copyright © 2000-2005 O’Reilly Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |

||||||||